- Home

- Raja Shehadeh

Palestinian Walks

Palestinian Walks Read online

'One way of measuring the quality of your freedom is to take a walk. Raja Shehadeh records how brutalizing the loss of a landscape is, both to the losers and the takers: there are no winners. Palestinian Walks is a stoic account of a particular place, but one which has universal resonance. The judges felt it made landscape into the essence of politics, and political writing into an art.' Jean Seaton, chair of the Orwell Prize committee, 2008

'It is impossible to capture the isolation felt by many Palestinians, but Shehadeh does a tremendous job … this may well be one of the most compelling things you'll read' Scotland on Sunday

'He distils his pain and anger into eloquent prose, meticulously counting the ways he loves his land, allowing it to sing in evocations of grass, luminous in sunlight, a sea of poppies, low oregano bushes yielding their scene as he brushes past, scarlet cyclamens growing out of crevices, muted pink rock roses … Palestinian Walks is no trite exercise in myth-making or propaganda.' Sunday Tribune

'Shehadeh describes how the destruction of a beloved landscape mirrors the damage to Palestinian identity … lyrical nature-writing with understated political passion' Guardian

'Intensely political while avoiding the excesses of pure polemic, Shehadeh's account continually grapples with misconceptions and misinformation … There's such an eccentricity to his approach, commenting on dinosaur footprints in the rock one moment, challenging Israeli law the next … it's a remarkable way of going about things, delivering what many activists neglect to mention: the odd, slightly absurd details that really touch people; things that appear off-camera, away from news reports – things that seem real' Independent on Sunday

'Palestinian Walks provides a rare historical insight into the tragic changes taking place in Palestine.' Jimmy Carter

'Towards any proper understanding of history there are many small paths. This constantly surprising book modestly describes walking along certain paths which have touched the lived lives of two millennia. I strongly suggest you walk with him.' John Berger

'This is a beautiful book and a sad one.' Anthony Lewis

'Shehadeh writes beautifully, his language infused with a lyrical, melancholic sense of loss. An important record of a land marked by conflict that is changing every day' Sunday Telegraph

'Shehadeh is a man of real principle, one who clearly believes he does the most good by enduring with dignity in the land of his birth … Readers more accustomed to greyish newspaper generalities about the 'situation' would do well to reckon with the painful particulars of Shehadeh's account, which is at once gentle and angry, resolute and realistic.' The Nation

RAJA SHEHADEH is the author of the highly praised memoir Strangers in the House, and the enormously acclaimed When the Bulbul Stopped Singing, which was made into a stage play. He is a Palestinian lawyer and writer who lives in Ramallah. He is a founder of the pioneering, non-partisan human rights organisation Al-Haq, an affiliate of the international Commission of Jurists, and the author of several books about international law, human rights and the Middle East. Palestinian Walks won the Orwell Prize in 2008.

PALESTINIAN

WALKS

Notes on

a Vanishing Landscape

RAJA SHEHADEH

First published in Great Britain in 2007 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

London EC1R 0JH

www.profilebooks.com

Revised and updated in 2008

This eBook edition first published in 2009

Copyright © Raja Shehadeh, 2007, 2008

Photographs by John Tordai

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Typeset by MacGuru Ltd

[email protected]

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN: 978-1-84765-129-7

To my nephew and niece,

Aziz and Tala, with the hope that they will be

able to walk in the hills of Palestine.

CONTENTS

Map

Preface to the Second Edition

Introduction

Walk 1: The Pale God of the Hills

Walk 2: The Albina Case

Walk 3: Illusory Portals

Walk 4: Monasteries in the Desert

Walk 5: And How Did You Get Over It?

Walk 6: An Imagined Sarha

Epilogue: The Masked Shepherds

Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

PREFACE TO THE

SECOND EDITION

This new edition of Palestinian walks, Notes on a Vanishing Landscape includes a new seventh walk, sadly marked by a disturbing encounter with two young, masked Palestinians. Another of my walks, accompanied by a television crew re-tracing the first walk in this book, was interrupted by Israeli soldiers who rushed towards us, guns pointed, and proceeded to interrogate us in the open-air. Perhaps we were fortunate to escape unscathed. Firas Kaskas, a father of three young children, taking an afternoon stroll with his brother in the early winter was shot dead by soldiers stationed in the same post.

None the less, the Palestinian spring has brought its carpets of anemones and shy stands of cyclamen to the hills. As always, a group of friends and I walk together every Friday. We see the increasing sprawl of Israeli settlements that threaten the fragile and violated landscape, but still we sit under an olive tree in a quiet valley and look at the play of light and shadow on the terraced hills. I don't know why we continue to hope for a future for these hills; one friend even clings to the long view of geological time. But I know they are there, and we will continue to wander through the hills on our sarha.

INTRODUCTION

When I began hill walking in Palestine a quarter of a century ago, I was not aware that I was travelling through a vanishing landscape. For centuries the central highland hills of Palestine, which slope on one side towards the sea and on the other towards the desert, had remained relatively unchanged. As I grew up in Ramallah, the land from my city to the northern city of Nablus might, with a small stretch of the imagination, have seemed familiar to a contemporary of Christ. Those hills were, I believe, one of the natural treasures of the world.

All my life I have lived in houses that overlook the Ramallah hills. I have related to them like my own private backyard, whether for walks, picnics or flower-picking expeditions. I have watched their changing colours during the day and over the seasons as well as during an unending sequence of wars. I have always loved hill walking, whether in Palestine, the Swiss Alps or the Highlands and outlying islands of Scotland, where it was a particular joy to ramble without fear of harassment and the distracting awareness of imminent political and physical disasters.

I began taking long walks in Palestine in the late 1970s. This was before many of the irreversible changes that blighted the land began to take place. The hills then were like one large nature reserve with all the unspoiled beauty and freedom unique to such areas. The seven walks described in this book span a period of twenty-seven years. Although each walk takes its own unique course they are also travels through time and space. It is a journey beginning in 1978 and ending in 2007, in which I write about the developments I have witnessed in the region

and about the changes to my life and surroundings. I describe walking in the hills around Ramallah, in the wadis in the Jerusalem wilderness and through the gorgeous ravines by the Dead Sea.

Palestine has been one of the countries most visited by pilgrims and travellers over the ages. The accounts I have read do not describe a land familiar to me but rather a land of these travellers' imaginations. Palestine has been constantly re-invented, with devastating consequences to its original inhabitants. Whether it was the cartographers preparing maps or travellers describing the landscape in the extensive travel literature, what mattered was not the land and its inhabitants as they actually were but the confirmation of the viewer's or reader's religious or political beliefs. I can only hope that this book does not fall within this tradition.

Perhaps the curse of Palestine is its centrality to the West's historical and biblical imagination. The landscape is thus cut to match the grim events recorded there. Here is how Thackeray describes the hills I have so loved:

Parched mountains, with a grey bleak olive tree trembling here and there; savage ravines and valleys paved with tombstones – a landscape unspeakably ghastly and desolate, meet the eye wherever you wander round about the city. The place seems quite adapted to the events which are recorded in the Hebrew histories. It and they, as it seems to me, can never be regarded without terror. Fear and blood, crime and punishment, follow from page to page in frightful succession. There is not a spot at which you look, but some violent deed has been done there: some massacre has been committed, some victim has been murdered, some idol has been worshipped with bloody and dreadful rites.

(Notes of a Journey from Cornhill to Grand Cairo)

It is as though once the travellers took the arduous trip to visit Palestine and did not find what they were seeking, the land as it existed in their imagination, they took a strong aversion to what they found. 'Palestine sits in sackcloth and ashes,' Mark Twain writes. '… Palestine is desolate and unlovely … Palestine is no more of this work-day world. It is sacred to poetry and tradition – it is a dream-land' (The Innocents Abroad).

The Western world's confrontation with Palestine is perhaps the longest-running drama in history. This was not my drama, although I suppose I am a bit player in it. I like to think of my relationship to the land, where I have always lived, as immediate and not experienced through the veil of words written about it, often replete with distortions.

And yet it is in the unavoidable context of such literature that I write my own account of the land and the contemporary culture of 'fear and blood, crime and punishment' that blot its beauty. Perhaps many will also read this book against the background of the grim images on their television screens. They might experience a dissonant moment as they read about the beautiful countryside in which the seven walks in this book take place: could the land of perpetual strife and bloodshed have such peaceful, precious hills? Still, I hope the reader of this book will put all this aside and approach it with an open mind. I hope to persuade the reader how glorious the land of Palestine is, despite all the destruction that has been wrought over the past quarter of a century.

This long-running drama has not ended. The stage, however, has relocated to the hills of the West Bank, where Israeli planners place Jewish settlements on hilltops and plan them such that they can only see other settlements while strategically dominating the valleys in which most Palestinian villages are located. It is not unusual to find the names of Arab villages on road signs deleted with black paint by over-active settlers.

A sales brochure, for the ultra-Orthodox West Bank settlement of Emanuel, published in Brooklyn for member recruitment, evokes the picturesque: 'The city of Emanuel, situated 440 metres above sea level, has a magnificent view of the coastal plain and the Judean Mountains. The hilly landscape is dotted by green olive orchards and enjoys a pastoral calm.' Re-creating the picturesque scenes of a biblical landscape becomes a testimony to an ancient claim on the land.

Commenting on advertisements such as this, the Israeli architects Rafi Segal and Eyal Weizman perceptively uncover 'a cruel paradox': 'the very thing that renders the landscape “biblical”, its traditional inhabitation and cultivation in terraces, olive orchards, stone building and the presence of livestock, is produced by the Palestinians, whom the Jewish settlers came to replace. And yet the very people who cultivate the 'green olive orchards' and render the landscape biblical are themselves excluded from the panorama. The Palestinians are there to produce the scenery and then disappear.'1

The land deemed 'without a people' is thus made available to the Jewish citizens of Israel, who can no longer claim to be 'a people without a land'.

The Israel Exploration Society instructs its researchers to provide 'concrete documentation of the continuity of a historical thread that remained unbroken from the time of Joshua Bin Nun until the days of the conquerors of the Negev in our generation'. To achieve this, the intervening centuries and generations of the land's inhabitants have to be obliterated and denied. In the process history, mine and that of my people, is distorted and twisted.

Such an attitude fits perfectly into the long tradition of Western travellers and colonizers who simply would not see the land's Palestinian population. When they spared a glance it was to regard the Palestinians with prejudice and derision, as a distraction from the land of their imagination. So Thackeray describes an anonymous Arab village outside of Jerusalem thus: 'A village of beavers, or a colony of ants, make habitations not unlike those dismal huts piled together on the plain here …' (Notes of a Journey …).

I am both an author and a lawyer. From the early 1980s I have been writing about the legal aspects of the struggle over the land and appealing against Israeli orders expropriating Palestinian land for Jewish settlements. Here I write about one of these seminal cases. I also write about the disappointing outcome of the legal struggle to save the land for which I gave many years of my life. At the same time I explore the mystery of this divided place and my fear for its uncertain future.

Ever since I learned of the plans to transform our hills being prepared by successive Israeli governments, who supported the policy of establishing settlements in the Occupied Territories, I have felt like one who is told that he has contracted a terminal disease. Now when I walk in the hills I cannot but be conscious that the time when I will be able to do so is running out. Perhaps the malignancy that has afflicted the hills has heightened my experience of walking in them and discouraged me from ever taking them for granted.

In 1925 a Palestinian historian, Darweesh Mikdadi, took his students at a Jerusalem government high school on a walking trip through the rocky landscape of Palestine, all the way to the more lush plains and fertile valleys of Syria and Lebanon with their streams, rivers and caves. Along the way the group inspected the sites of the famous battles that were fought over the centuries in this part of the world, staying with the generous villagers who offered them hospitality. While the battles continue, it has been impossible since 1948 to repeat this journey.

During the 1980s, the Palestinian geographer Kamal Abdul Fattah would take his students at Birzeit University on geography trips throughout historic Palestine. One year I joined the students and we spent three exciting days travelling from the extreme fertile north of the land to its desert south, observing its topography and becoming familiar with its geological transformations and the relationship between geography, history and the way of life of its inhabitants. The trip was a great eye-opener for me. Since 1991 after restrictions were imposed on movement between the West Bank and Israel that journey too has become impossible.

The Gaza Strip has become completely out of bounds for Palestinians from the West Bank. A merchant from Ramallah finds it easier to travel to China to import cane garden chairs than to reach Gaza, a mere forty-minute drive away, where cane chairs, once a flourishing industry, now sit in dusty stacks. The settlement master plans published in the early eighties that I write about, which called for separate enclaves for the Pa

lestinians, were being systematically implemented. To wrap up these inhuman schemes came the Separation Wall, which was not designed to follow the border between Israel and the West Bank but to encircle the 'settlement blocs' and annex them to Israel, in the process penetrating the lands of the Palestinians like daggers. As a consequence of all these developments even shorter school trips have now become restricted, so students can only repeat forlorn visits to the sites within their own checkpoint zone. The Palestinian enclaves are becoming more and more like ghettos. Many villagers can only pick the olives from their own trees with the protection of sympathetic Israelis and international solidarity groups. On Election Day in 2005 a young man selling sweets told me he was not going to vote. 'Why should I when I have not been able to leave Ramallah for five years now? How would these elections change that?' As our Palestinian world shrinks, that of the Israelis expands, with more settlements being built, destroying for ever the wadis and cliffs, flattening hills and transforming the precious land which many Palestinians will never know.

In the course of a mere three decades close to half a million Jewish people were settled within an area of only 5,900 square kilometres. The damage caused to the land by the infrastructural work necessary to sustain the life of such a large population, with enormous amounts of concrete poured to build entire cities in hills that had remained untouched for centuries, is not difficult to appreciate. I witnessed this complete transformation near where I grew up and I write about it here. Beautiful wadis, springs, cliffs and ancient ruins were destroyed, by those who claim a superior love of the land. By trying to record how the land felt and looked before this calamity I hope to preserve, at least in words, what has been lost for ever.

Going Home

Going Home Where the Line is Drawn

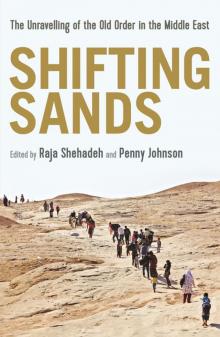

Where the Line is Drawn Shifting Sands

Shifting Sands Palestinian Walks

Palestinian Walks Shifting Sands: The Unravelling of the Old Order in the Middle East

Shifting Sands: The Unravelling of the Old Order in the Middle East